In the Information Age, the quest for knowledge and understanding of the world has been greatly elevated by the ability to exploit the exponential growth and falling costs of computational power. Welcome to big data – generated from our digital footprints as we negotiate our way through early 21st century life.

Recent developments in cloud and open source computing have been central to unravelling a range of secrets that would otherwise have remained hidden – from genetic sequencing, courtesy of the Human Genome Project, to deconstructing mysteries of the universe via the Large Hadron Collider. These and other significant attempts at understanding the human condition are predicated on the ability to store and rapidly query trillions of bytes of structured and unstructured records to analyze any relationships among its diverse datasets and confirm/deny hypotheses.

What is it?

Opinions on what constitutes big data may vary, but technology analyst and big data evangelist Edd Dumbill’s contribution to the list does cover the types of dataset prompting massive financial investment by companies wishing to exploit it: “Social networks, web server logs, traffic flow sensors, satellite imagery, broadcast audio streams, banking transactions, MP3s of rock music, the content of web pages, scans of government documents, GPS trails, telemetry from automobiles, financial market data – the list goes on.”

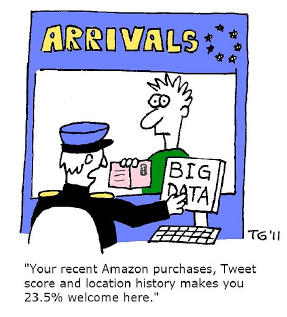

Image from Thierry Gregorious

Already embraced within the specialist worlds of finance, healthcare, sports, urban planning, and government (where the U.S. National Security Service’s penchant for modern day data processing techniques was recently exposed), big data use is increasingly trickling down to mainstream business sectors to companies both large and small. All are determined to acquire masses of previously unobtainable data and mine it for nuggets of insight into customers’ habits, which they hope will boost profitability and product development. Computer services giant IBM has dubbed big data “the next natural resource” and technology analyst firm IDC predicts a 35% rise in corporate expenditure on big data tools.

As the saying goes, knowledge is indeed power. But another saying – “power is seductive,” is a timely reminder that on occasion, power can ride roughshod over understanding, crowding out all alternatives. And it seems to me that there is a fear that the big data concept, with its promises of more answers and more profits, is doing just that – bulldozing its way through previously tried and tested methods of business intelligence gathering.

From the eyes of an anthropologist

Before I proceed any further, there is a disclosure I must make: as a qualified anthropologist – trained to gain insights into human behavior by directly observing and questioning people first-hand about how they relate to and understand the world around them – the idea of getting a deeper appreciation of what we do and why by crunching numbers alone would always be problematic.

Late eminent social anthropologist Clifford Geertz’s concept of “thick description” denotes the need for interpretation of cultural phenomena as experienced within their social context, alongside observation: is a wink just an abstract eye movement? Or a gesture of familiarity, romantic inclination or any other social indication? The point is that you need to get in among the people to see meaning in the things we actually do, beneath the surface of (and in many cases at odds with) what we say we do.

The advertising and marketing industry, among others, has a long history of deploying qualitative, face-to-face, social research to observe and gain insight into people’s actual behaviors, rather than just imprints of that behaviour, which is all that big data analytics can be capable of providing. While imprints can be useful, as examples will show, away from any qualitative input or social context, they literally tell only half the story. As such, the problems with the rising prominence of big data from my vantage point are three-fold:

1. The hubristic idea in some circles that “with enough data, the numbers speak for themselves.” In other words, more data equals better data, allowing us to discard other tried and tested measures for analyzing human behavior, such as statistical significance. Through this type of “data fundamentalism,” an almost blind faith in big numbers is attempting to change the very meaning and definition of how we acquire knowledge. There is no denying that through sheer processing power, big data analytics are capable of drilling down into petabytes of the stuff to come up with useful, actionable information. But for some, the bigger the data sets become, the less they see pitfalls of bias and false correlations in the data.

A segment of big data currently fueling analytical interest among companies looking to extract insight from our online behavior, is what has become known as “data exhaust.” This refers to the unstructured, digital traces of our online searches, tweets, mobile phone logs and signals, etc., that trail behind our each and every electronic interaction in our business and social lives.

Kate Crawford, principal researcher at Microsoft, has looked extensively at the inherent bias within these “found data” sources. She regularly cites the example of how the U.S city of Boston harnessed big data in order to rid its streets of potholes. The Mayor’s office released Streetbump, a smartphone app, which used the built-in GPS and accelerometer to automatically report the instance and location whenever a user travelled over a dip in the road. But the flaw in this innovative but ultimately misjudged data gathering exercise was that the likely demographic of smartphone users in the city – i.e. the relatively young and affluent – were only a subset Boston’s citizens. More data in this case gave more bias and distortion and less clarity.

2. Too many conversations about what big data can achieve are being had away from actual human experience, the details of which they purport to capture. There are indeed commercial examples where mining multiple data sets has revealed information that can be usefully fed directly into strategy. But the following example also shows what happens when context-rich, qualitative analysis is substituted completely. This New York Times piece relates to U.S. retail giant Target’s big data strategy, in which it used the technology to (accurately) predict and identify pregnant customers – the demographic most open to changing their buying habits statistically and therefore most receptive to sales pitches – the company believed. Once identified, these customers were plied with various offers and discount vouchers through the post.

Unfortunately for Target, its quantitative accuracy literally left the human out of the equation: the retailer’s initial enthusiasm at success was dampened when the father of a customer still at high school angrily protested to the company for sending his daughter shopping vouchers for baby items. It turned out that Target had gained knowledge of the girl’s pregnancy before her parents did. But the company ultimately confused knowing about customers with knowing them.

ZN for one has advocated the need for clients and businesses in general to keep authenticity at the forefront of their dealings with their stakeholders for some time. Customers are demanding it in their everyday experiences and increasingly in their commercial transactions. Without it, you cannot truly engage with the customer now. And it won’t be achieved by compiling data about them, without ever entering their world.

3. There’s a sense of entitlement among some companies that the data is theirs for the taking. For them, there is no hesitation that the data is there to be harvested and in some cases sold on, with precious few discussions about privacy, ownership or the need for negotiation with those to whom the data relates. Engagement with the people rather than just their data proxies, would reveal that there are two types of customer – those for whom privacy is paramount and non-negotiable, and those willing to trade their data to varying degrees.

The creepiness factor in the Target example stems from the fact that customers are often unaware of companies’ ability to track, predict and reveal their behaviour, and with such precision (of course those supermarket rewards cards have been around for ages…). In Target’s case it was to sell more nappies and baby shampoo. With other firms or government bodies, their motivations could be far more unsettling.

Private vs. public

The issue of what personal data should be freely available has come to the fore in recent weeks, after the European Court of Justice backed individuals’ right to be forgotten online. This means that, at the subject’s request, search engines like Google and Bing must remove outdated or “irrelevant” information about them. Altering “history” so to speak.

It’s another classic case of the law falling woefully behind innovation… but it also illustrates the fine balance businesses must keep so as not to be corrupted by the immense knowledge-led power they are beginning to possess. Legal ramifications aside, what will it all matter if you lose your customer’s trust? Is it worth losing everything?