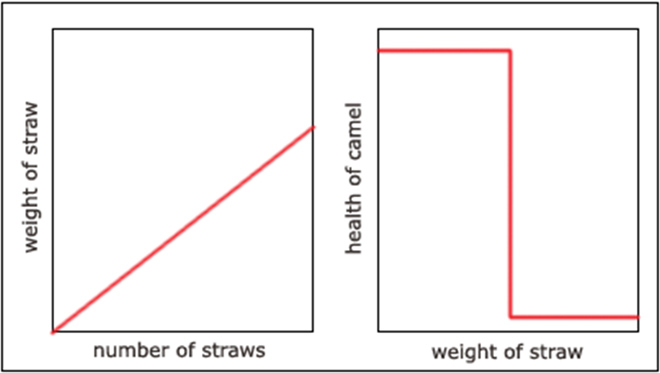

The term “tipping point” has been in circulation since the 1950s. In the study of economics, physics, sociology, or climate change, it means the point at which slow steady change becomes irreversible.

The classic graph of the tipping point measures the addition of hypothetical straws onto the back of a hypothetical camel.

A look at Google Ngram viewer shows that the term had a huge increase in usage starting around 2000 and continues to this day.

The graph does not show the extreme right angle bend associated with the “tipping point” graph, but it is still remarkable, and more remarkable still because it is attributable to one man, Malcolm Gladwell, whose book The Tipping Point became a global phenomenon and an example of the kind of “social epidemic” described in the book. This seems fitting.

In the book, Gladwell describes what he calls the law of the few: “The success of any kind of social epidemic is heavily dependent on the involvement of people with a particular and rare set of social gifts.”

He describes three particular kinds of vectors for social epidemics: Connectors, Mavens and Salesmen. Connectors are extremely sociable people, who enjoy making introductions and act as the hub of a social network. Mavens are information brokers, experts in a certain field who spread their knowledge. And Salesman are just that: persuaders who exert a disproportionate influence in promoting an idea.

Gladwell’s thoughts on social epidemics are not dissimilar to Richard Dawkins’ ideas about memes, as he himself has admitted, and it’s interesting to observe that, broadly speaking, Gladwell’s three categories correspond to the three qualities Richard Dawkins mentions as important to the spread of a gene (or meme): connectors promote the longevity of an idea by extending its influence across a network; salesmen sell, promoting an idea or trend’s greater fecundity; and mavens, through their detailed knowledge of a subject, ensure the fidelity to the original of each version or generation of an idea.

Gladwell’s thoughts on social epidemics are not dissimilar to Richard Dawkins’ ideas about memes, as he himself has admitted, and it’s interesting to observe that, broadly speaking, Gladwell’s three categories correspond to the three qualities Richard Dawkins mentions as important to the spread of a gene (or meme): connectors promote the longevity of an idea by extending its influence across a network; salesmen sell, promoting an idea or trend’s greater fecundity; and mavens, through their detailed knowledge of a subject, ensure the fidelity to the original of each version or generation of an idea.

It’s not surprising that the language of the spread of ideas consistently refers to the spread of disease: Gladwell discusses social epidemics; we talk of virality. There has been very interesting work done on epidemiology and networks, and the way an idea spreads can easily be likened to a disease. Gladwell himself mentions Gaetan Dugas, “Patient Zero” for AIDs, as a good example of a ‘connector’.

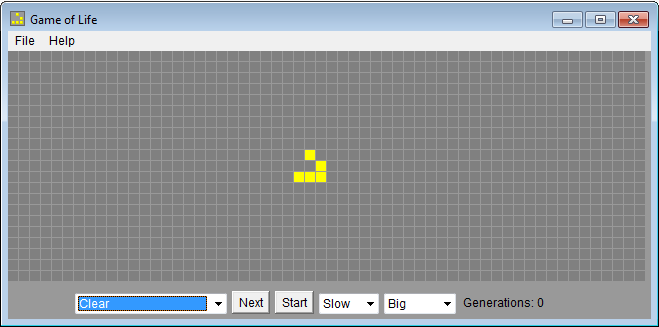

But one thing that the spread of ideas and diseases has in common is complexity, as can be seen in John Conway’s famous Game of Life, or Langton’s Ant, where simple rules produce complex patterns.

This suggests that although we can identify certain elements that go to make up a trend, a virus, or a social epidemic, it is difficult to predict one or to engineer one reliably. Gladwell suggests that one thing that makes a difference is the stickiness factor, the specific content of a message that renders its impact memorable.

This sounds vague, and it can be hard to pin down what makes an idea sticky, but one powerful and universal tool is story.

Stories & narratives

Stories add emotion to raw data, and we naturally respond to and remember information when it is given to us in terms of a narrative. In fact, it is this very quality that distinguishes Malcolm Gladwell: that his thoughts about social trends are always put in terms of very clear and engaging narratives. This is his particular skill (his sticking point perhaps): that he can find the story in the data and can present an abstract idea in terms of clear and engaging narrative.

There is no more famous story in US history than that of “The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere.” Gladwell uses the story to illustrate his point about connectors, and he does it in a way that depends on the stickiness of the story itself. Similarly he hitches his theory to vivid emotive stories about teenage suicide in Micronesia, or the rise of Hush Puppies in New York. He doesn’t make it explicit but the secret weapon in making The Tipping Point as much of a social epidemic as the ones it describes, is story.

In fact, it is tempting to suggest that Gladwell is not so much a maven for the idea of the tipping point as a salesman. And if we want to create a buzz, developing a good story is vital.

We can be aware of other factors in trying to create social trends. We can make sure to work with the right people – connectors, mavens, salesman – but if you want your idea to spread and reach epidemic proportions, it’s still essential to have a compelling story to tell.